Cats and Dogs in Morocco

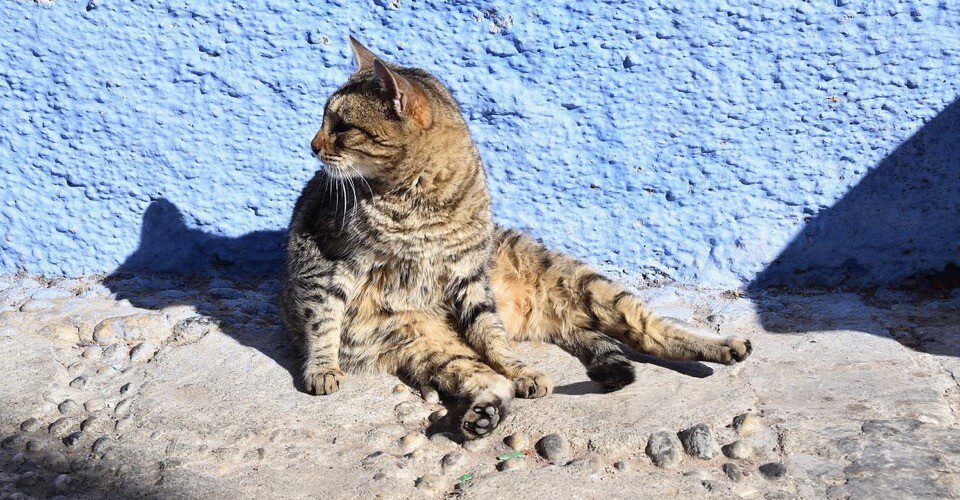

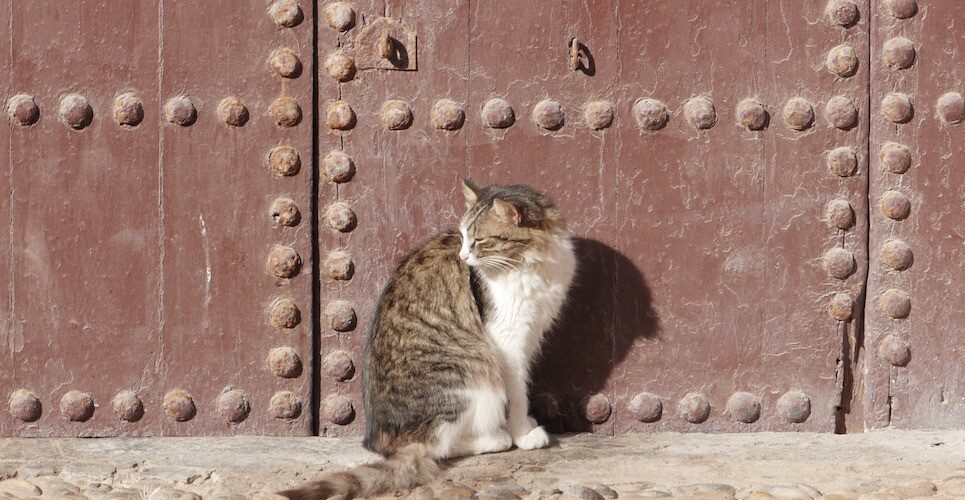

In Morocco, cats are the true masters. From the labyrinthine alleys of Tangier to desert camps on the Sahara’s edge, these furry residents are everywhere—they lounge lazily on the zellij-tiled steps of mosques, leap nimbly over Fez’s dye pits, groom themselves on Chefchaouen’s blue stairways, and even patrol Marrakech’s night market stalls with unshakable confidence.

As sacred creatures in Islamic culture, cats hold special status in Morocco. The Quran tells how Prophet Muhammad cut off his sleeve to avoid disturbing a sleeping cat, a respect passed down through millennia that makes felines the most beloved companion animals. You can:

Purchase dedicated cat food from local shops for street feeding

Support “community cat” sterilization programs through local animal protection organizations

Seek out cat-themed riads and cafés in ancient cities like Tetouan

When sunset gilds the Hassan II Mosque and feline silhouettes grace the skyline alongside minarets, these free spirits will become the warmest verses in your Moroccan memories.

Religious origin

In Moroccan culture where religion permeates daily life, understanding customs requires tracing back to Islamic teachings. Moroccans follow two primary religious foundations: the Quran as divine revelation, and the Sunnah—a collection of precepts based on the Prophet’s sayings and deeds recorded by his disciples, known as “Hadiths.” It is the latter that has shaped the distinctive cultural attitudes toward cats and dogs.

The Quran makes no direct mention of cats and references dogs only three times, focusing solely on their hunting and guarding abilities. The Hadiths, however, contain clear distinctions: they record how Prophet Muhammad chose to cut off his sleeve rather than disturb his sleeping cat Mu’izza, and how he instructed that containers licked by dogs must be washed seven times (one of which should involve soil), while no special cleansing is required for vessels touched by cats. These records gradually fostered the popular belief in “feline purity and canine impurity,” allowing cats to freely enter mosques, markets, and homes as the only animals permitted to sleep on prayer rugs.

Islam’s emphasis on cleanliness constitutes a wisdom system integrating faith and public health. Taking ablution (wudu) before prayers as an example, this ritual not only symbolizes spiritual purification but was also a groundbreaking practice for preventing disease transmission in 7th-century Arabia—the repeated washing with running water, along with cleaning the mouth and nasal cavity, effectively blocked infection chains during communal mosque prayers.

This philosophy linking hygiene with religious devotion directly shapes attitudes toward animals. Cats are considered “self-purifying creatures” due to their daily grooming and waste-burying instincts, while dogs require stricter cleaning procedures because of their omnivorous habits and differing saliva microbiota. In Morocco today, you’ll observe:

Traditional families allowing cats to wander beneath kitchen tables

Most pet dogs kept in courtyards, requiring paw cleaning before entering homes

Market vendors cleaning cats’ ears with rosewater before sale

From a medical perspective, these practices align with modern hygiene principles: the barbed structure of cats’ tongues naturally removes parasites, while enzymes in canine saliva do necessitate more thorough cleaning. This millennia-old lifestyle wisdom creates a delicate balance between religious observance and scientific understanding in Moroccan daily life.

But is it true that cats tend to be cleaner than dogs?

While cats spend hours each day meticulously grooming with their barbed tongues, they are performing an ancient self-purification ritual—this not only removes fleas and lice but also maintains skin microbiome balance through salivary enzymes. Meanwhile, dogs as a wolf subspecies retain their ancestors’ survival wisdom: rolling in dirt isn’t mere play but sophisticated camouflage using mineral powders to neutralize scent; seemingly mischievous digging actually represents genetic memory of concealing odors to avoid alerting prey.

That furry companion you call by an affectionate name at home still carries the wild in its heart. A cat’s arched back and bristled fur recreates the body-size exaggeration strategy used against predators. Even the gentlest pet’s eyes still gleam with predator’s fluorescence in the dark

Current situation

Islamic oral tradition preserves a cherished story of the Prophet and his feline companion: One day, as Prophet Muhammad prepared to rise for prayer, he found his beloved cat Mu’izza sleeping peacefully on his robe. Unwilling to disturb the creature’s slumber, he carefully cut away the section of his garment trapped beneath the sleeping cat, choosing to perform the sacred ritual in his damaged robe rather than wake the animal. Though not recorded in the official Hadith collections, this anecdote passed down through generations serves as a cultural prism refracting Islam’s profound respect for all living beings.

This severed garment has since been interpreted by believers as containing multiple symbolic layers:

The subordination of material concerns to spiritual values—the integrity of clothing matters less than the peace of a living creature

Gentleness as strength—the most delicate considerations often reveal the truest essence of faith

Symbiotic wisdom—the right of humans and natural beings to share sacred spaces

Cultural narratives about dogs present more complex dimensions. Legends speak of desert strays detecting shallow-buried remains—this actually corresponds to Berber burial practices: nomadic tribes initially used shallow graves until discovering remains were excavated by wildlife, leading to deeper burials or tomb caves. This association with death rituals has cast a particular shadow over dogs in the cultural subconscious.

Moroccans’ preference for cats is deeply rooted in their unique community consciousness. In this civilization that holds “Ummah” (community unity) as paramount:

Cats serve as mobile connectors crossing household boundaries, freely moving through shared neighborhood courtyards

Their independence mirrors Moroccan social structure—maintaining individual freedom while preserving group bonds

The tradition of collectively feeding stray cats becomes a daily ritual practicing communal responsibility

When you see elderly women preparing dinner for entire alleyways of cats in Fez Medina, or witness vendors and tourists jointly rescuing injured felines in Marrakech’s square, you understand: these furry creatures are not just pets but living metaphors sustaining Morocco’s social fabric.

Moroccans’ choice of companion animals reflects a unique community philosophy: they prefer cats with greater autonomy—these graceful creatures move freely between mosque domes, market stalls, and residential courtyards, becoming mobile connectors linking the city’s capillaries. As the ancient saying in Fez goes: “Cats belong to Allah, we are but their caretakers.” Here, cats rarely have exclusive owners but enjoy the collective care of the entire community.

When you see cat colonies leaping through golden sunset light, you’ll understand how this free-roaming life form perfectly resonates with Morocco’s national character of “openness containing mystery.”

Contact us for more travel information!