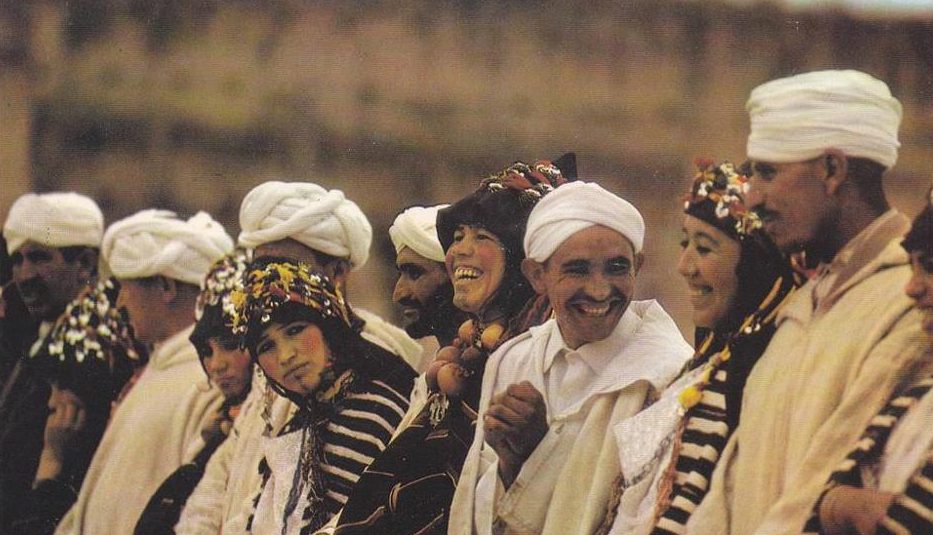

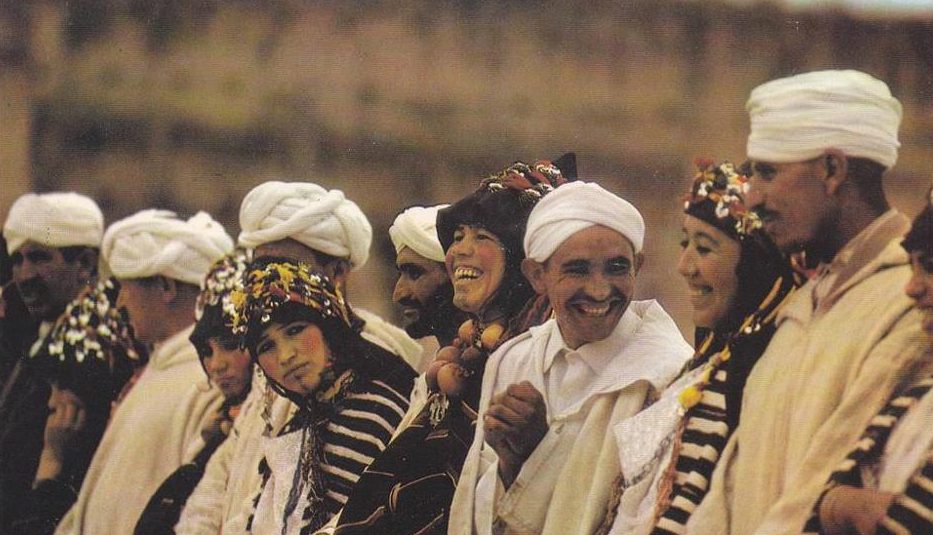

Berber New Year in Morocco

Yennayer—the Berber New Year celebration passed down through generations—stands as the only non-Muslim holiday shared universally across North Africa. As the calendar turns to January 12th (or 13th in leap years), from the foothills of the Atlas Mountains to the fringes of the Sahara, each Berber community awakens ancient traditions in its distinctive way: the Rif mountain people hide lentils among grains to pray for abundance, women in the Souss Valley adorn their hands with henna patterns symbolizing life, and desert tribes gather around bonfires chanting the creation epic “Halili.” During the universal New Year’s feast, seven traditional dishes mirror the seven stars of the Big Dipper, while the aroma of almond lamb stew intertwines with the sweetness of date pastries, continuing a calendrical tradition that began in 950 BCE under candlelight.

A little history

Berber civilization traces its roots back to 10,000 BC, yet its official calendar begins in 950 BC—when the Berber king Sheshonq I was crowned Pharaoh of Egypt, founding the Twenty-Second Dynasty that ruled until 715 BC. This historical event, recorded in the Hebrew Bible, provides the first written evidence establishing a timeline for Berber history.

Each Gregorian January 12th (or 13th in leap years) marks the Berber New Year, Yennayer. Like Russia’s Maslenitsa, Chinese Spring Festival, and Arabic Eid, the Berbers developed an ancient calendar synchronized with natural cycles: they determined sowing seasons by the Pleiades’ movement, judged pasture abundance by fig tree budding, and prepared new year rituals at the third new moon after winter solstice. Long before Julius Caesar implemented the Julian calendar, North African nomads were already charting agricultural cycles in the sand by observing the angular relationship between Sirius and the sun.

The Celebration of Yennayer

In Berber culture, Yennayer is first and foremost a sacred threshold known as ‘tabburt useggwass’ (the door of the year). The profound significance of this celebration stems from ancient agricultural wisdom—it arrives as winter provisions near depletion and spring vitality awaits release, requiring purification rituals to channel new spiritual strength into the land and life.

Rituals preserved to this day overflow with symbolism: housewives sprinkle courtyards with wild fennel water to dispel stagnant energy from the past year; farmers polish plowshares until they gleam and carve geometric patterns on thresholds to invoke abundance; children receive painted clay rattles, their chimes believed to awaken dormant soil. During the grand “Feast of Plenty,” seven almonds are hidden in a pot of coarse wheat porridge—those who find them are granted year-round blessings. These seemingly simple acts represent a profound covenant between humanity and nature: when we honor the turning of time with reverence, the earth responds with resonant generosity.

Rituals

To welcome a prosperous new year, the Berber people perform a series of purification rituals: thoroughly cleaning their homes, smudging dwellings with fresh herbs, and sweeping room by room to dispel energies of scarcity. These acts symbolize the expulsion of evil spirits and negative forces, making space for benevolent powers that will protect the household.

When means allow, families sacrifice livestock according to the number of household members—tradition dictates sacrificing one rooster for each man, one hen for each woman, and two for pregnant women to include the unborn child. If meat is unavailable, each family member is represented by an egg, maintaining the ritual connection to ancestors through simple means. As sacrificial blood soaks into the earth and eggs are stacked into small towers before thresholds, these millennia-old ceremonies continue to whisper the most ancient covenant between humanity and the natural divine.

Meal

For this significant occasion, every Berber family shares a special dish of couscous with chicken, distinctly more abundant than everyday meals. The golden semolina is piled high like a miniature mountain, surrounded by seven seasonal vegetables, while the whole chicken is deconstructed and reassembled into a spreading-wing formation—all symbolizing wishes for a bountiful coming year.

The feast inevitably includes symbolic sweets: almond crepes drizzled with wild honey, sesame-coated fried dough balls, and dried figs aged in traditional clay jars. Following ancient custom, the New Year’s dinner begins only when stars and moon grace the night sky. Elders distribute the sacrificial animal’s liver to children for wisdom and the shoulder meat to youth for strength. The most touching tradition is the mother setting out silver spoons for absent loved ones—those traveling far away still participate in the family’s energy cycle through meticulously arranged cutlery and reserved portions on the communal plate, reuniting the household’s strength across oceans at the dinner table.

After the feast, the family matriarch (the grandmother or mother) solemnly asks the children, “Has hunger been vanquished?” The children must chorus in response: “Becqua Neswa (Yes, we have eaten and are satisfied).” This Berber phrase, passed down through generations, symbolizes leaving material scarcity forever in the old year. If a child fails to finish their meal, the mother quietly wraps the leftovers and tucks them into the child’s pocket—not as reproach, but as a portable blessing of abundance.

The festival’s resonance lingers in the days that follow: sacrificial bells made from animal horns chime softly under the eaves, the scent of spices lingering in the courtyard mortar transforms daily, and coarse semolina clinging to children’s clothes becomes their ticket to receive sweets from neighbors. These ritualistic moments woven into life’s fabric make the transition between years as natural as plant growth—a gratitude for nature’s gifts and a celebration of the cycle of life itself.

Berber New Year Traditions

As a symbol of life’s cyclical renewal, Yennayer is intrinsically woven into pivotal moments of Berber life:

A Boy’s First Haircut: The grandfather buries the child’s first locks under an olive tree, praying for wisdom to grow alongside the tree

Wedding Blessings: Newlyweds share a bowl of seven-grain porridge, tracing concentric patterns on each other’s foreheads with wheat kernels

Agricultural Initiation: Elders take children to newly awakened fields to harvest the first greens as offerings to the hearth deity

In the Atlas Mountains, children don handmade masks for door-to-door visits—falcon-feather masks embody courage, clay demon masks ward off misfortune, and woven sun masks invoke bounty. When these little spirits return with aprons full of dried fruits and candies, they carry not just sweets but the community’s collective blessings for the new generation.

Contact us for more travel information!