Jewish Heritage in Morocco

Morocco stands as a rare beacon of Jewish-Muslim coexistence in North Africa, where Hebrew prayers have echoed for two millennia alongside the call to prayer. This extraordinary heritage manifests through vibrant sites and living traditions.

Fes Mellah: A Journey Through the World’s Oldest Jewish Quarter

Tucked away within the sprawling medina of Fes, the Mellah is not merely a district; it is a living chronicle etched in stone and memory. Established in 1438, it holds the distinguished title of the world’s oldest preserved Jewish quarter, offering a profound glimpse into centuries of Sephardic Jewish life, faith, and resilience under the protection of Moroccan sultans.

Origins and the Meaning of “Mellah”

The founding of the Fes Mellah was a pivotal moment in the 15th century. The ruling Marinid or Wattasid sultan, seeking to protect the city’s Jewish population from periodic unrest while also bringing them under closer royal supervision, ordered the creation of this walled enclave. The name “Mellah” is Arabic for “salt,” and its origin is steeped in local lore. Some believe it derives from the area’s former use as a salt market, while a more poignant theory suggests it was the site where the bodies of traitors were salted and displayed—a stark reminder of the quarter’s complex relationship with the wider city.

An Architectural Poem in a Labyrinth

This vertical, outward-facing design was no accident. It was a practical and social response to limited space, allowing for dense habitation while providing a vital interface with the community. The balconies served as open-air living rooms where women could observe the street life, converse with neighbors, and enjoy the breeze while maintaining a degree of privacy. As sunlight filters through the geometric patterns of the woodwork, casting shifting shadows on the weathered walls, the area feels both mysterious and poetic. At its zenith, this compact neighborhood was a vibrant hub of Jewish life, with an astonishing 19 synagogues once operating within its confines, their walls echoing with the whispers of prayer and the chanting of sacred texts.

A Monument of Faith: The Ibn Danan Synagogue

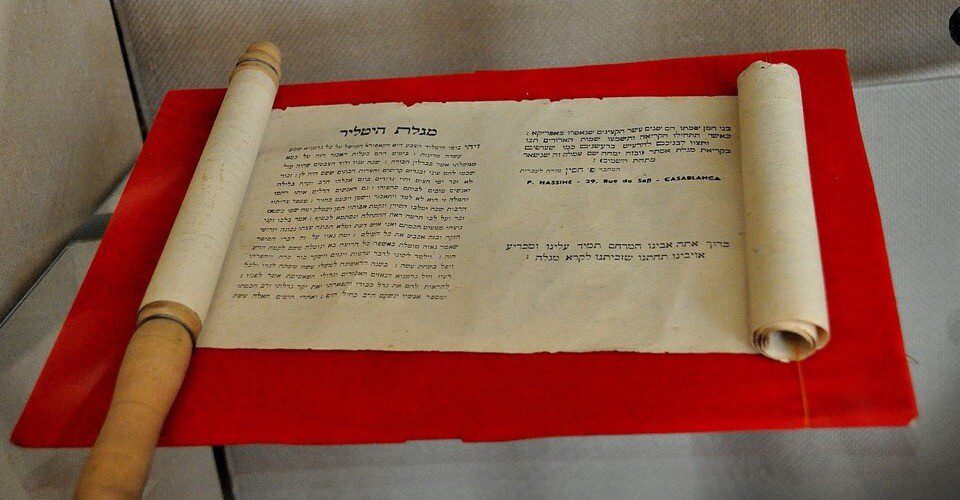

Stepping inside is like entering a suspended moment in time. The interior is not grand in scale but is overwhelming in its aura of solemn and intimate devotion. The walls are adorned with original Hebrew inscriptions, and at its heart stands an exquisite Holy Ark (Heikhal), safeguarding centuries-old, original Torah scrolls. These parchment scriptures are not only sacred religious objects but also priceless historical artifacts, their meticulous script still legible, speaking to an unbroken chain of faith.

Yet, the synagogue’s deepest secret lies beneath its stone floor: a remarkably preserved, underground mikveh (ritual bath). Hewn from the natural rock, this pool of living water, essential for purification rites, has witnessed countless cycles of spiritual renewal for generations. Descending its cool, stone steps into the hushed, damp air offers a tangible and moving connection to the ancient traditions that once thrived here.

Echoes in the Present Day

Today, the Mellah remains a bustling residential quarter, even as its Jewish community dwindled following the large-scale emigration of the mid-20th century. Its streets are a vibrant tapestry where traditional Jewish goldsmith shops stand shoulder-to-shoulder with spice vendors and tailor workshops. The ornate balconies of Jewish architecture coexist with Arabic-style doorways, creating the unique and harmonious cultural mosaic that defines Fes.

The Fes Mellah is more than a tourist destination; it is a living museum and a testament to the coexistence of civilizations in a specific time and place. To walk its streets is to run your fingers over the grooves of history, where every carved detail and weathered stone holds a story centuries in the making, waiting for the attentive visitor to listen.

The Marrakech Mellah: An Oasis of Andalusian Grace

Established in 1558 by order of Sultan Moulay Abdallah al-Ghalib, the Marrakech Mellah represents a later, yet equally significant, chapter in the history of Morocco’s Jewish communities. Unlike the ancient, vertically-built quarter of Fes, the Marrakech Mellah was conceived with a different sensibility, characterized by wider streets and a more open feel, reflecting its location near the royal Kasbah and its role as a protected, yet integral, part of the Ochre City.

A Foundation of Protection and Prestige

Architectural Harmony and the Spirit of the Souk

The urban fabric of the Marrakech Mellah is distinct. While it retains the labyrinthine charm typical of Moroccan medinas, its main thoroughfares are noticeably broader, originally designed to accommodate a different pace of life and commerce. The architecture seamlessly blends Moroccan and Jewish influences, with homes featuring characteristic wrought-iron balconies and wooden screens (mashrabiya) that overlook lively market streets.

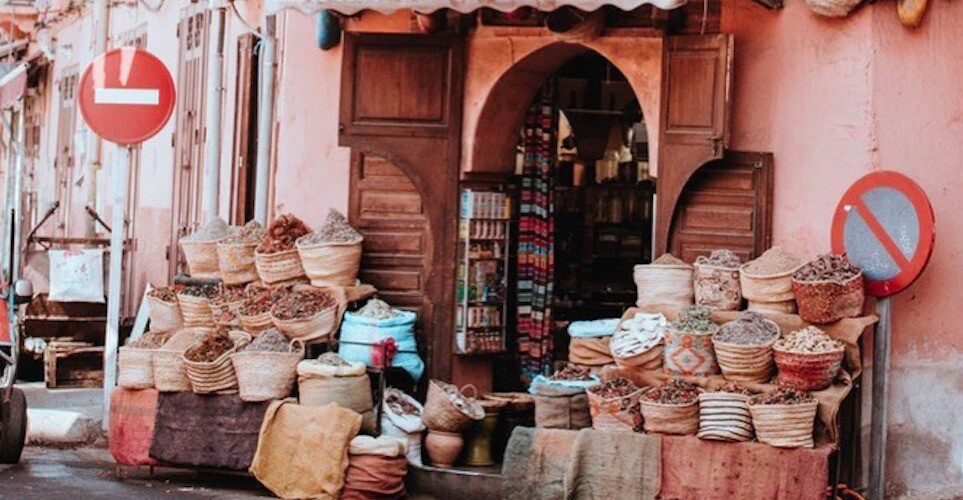

Today, the Mellah is the vibrant heart of the city’s spice trade. The air is thick with the scent of saffron, cumin, and dried petals, and the streets are a cacophony of color from mounds of turmeric, paprika, and countless other herbs. This bustling souk atmosphere contrasts with the serene, hidden worlds within its unassuming walls.

The Lazama Synagogue: A Courtyard of Memory

Tucked away down a quiet alley, the Lazama Synagogue (Slat al-Azama) is the spiritual and historical cornerstone of the quarter. Founded by Jews who were expelled from Spain in 1492 and later found refuge in Marrakech, the synagogue stands as a living monument to the Sephardic diaspora.

Entering the synagogue is a transformative experience. The prayer hall itself is beautifully appointed, with polished silver menorahs, rich textiles, and elegant wooden pews. However, its true soul is its central, sun-drenched Andalusian courtyard. This serene space, surrounded by graceful white arches and adorned with climbing bougainvillea, evokes the lost patios of Andalusia. It serves as a tranquil gathering place and a powerful architectural echo of the homeland the community left behind.

The synagogue also houses a small but profoundly moving museum that meticulously documents the Sephardic migration and the subsequent life of the community in Morocco. Through black-and-white photographs, traditional costumes, marriage certificates (ketubot), and sacred objects, the exhibition narrates a story of exile, adaptation, and cultural preservation. It connects the dots from the traumatic expulsion from the Iberian Peninsula to the flourishing, if sometimes challenging, life within the walls of the Marrakech Mellah.

A Living Tapestry

While the Jewish population of Marrakech has significantly decreased, the Mellah is far from a relic. It remains a dynamic and densely populated neighborhood, where Muslim and Jewish families continue to live side-by-side. The Lazama Synagogue is still an active house of worship, its prayers a testament to a enduring legacy. The neighborhood is a palimpsest, where the scents of the spice souk, the quiet dignity of the synagogue courtyard, and the everyday life of its residents weave together the past and present.

The Marrakech Mellah offers a different narrative than its counterpart in Fes—one not of ancient, shadowed lanes, but of sunlit courtyards and the enduring spirit of a community that carried the elegance of Andalusia into the heart of North Africa.

Essaouira Mellah: The “Little Jerusalem” by the Sea

Nestled within the wind-swept, fortified walls of the coastal city of Essaouira, the Mellah tells a unique story of commerce, coexistence, and cultural zenith. Unlike the older, more introverted quarters of Fes and Marrakech, Essaouira’s Jewish district, once proudly known as “Little Jerusalem,” was a vibrant and integral economic engine of a city designed for global trade. Founded in the 18th century under the visionary Sultan Sidi Mohammed Ben Abdallah, it represented a brief but brilliant golden age.

A Sultan’s Vision: The Rise of “Little Jerusalem”

Masters of the Maritime Trade

The lifeblood of the Essaouira Mellah was the sea. Its residents were the undisputed masters of the city’s maritime trade, forming a powerful merchant class known as the Tujjar al-Sultan (the Sultan’s Merchants). From their offices and homes in the Mellah, they orchestrated a complex web of commerce, negotiating with European consuls and Saharan caravans alike. They exported almonds, olive oil, and precious Saharan gold, and imported textiles, sugar, tea, and firearms. The narrow streets would have been filled with the sounds of multilingual bargaining, the scent of exotic goods, and the air of cosmopolitan enterprise, making it a true mercantile powerhouse on the Atlantic coast.

The Slat Lkahal Synagogue: A Restored Jewel

For decades, like much of the Mellah, the synagogue fell into a state of graceful decay as the community dwindled. However, a recent and meticulous restoration has breathed new life into its sacred halls. The most stunning feature to re-emerge is its exquisite blue-and-white stuccowork. This intricate plaster carving, known as gebs, now shines with its original, fresh color palette. The designs—featuring floral motifs, Stars of David, and intricate geometric patterns—evoke the sea, the sky, and the city’s distinctive blue-shuttered windows. This restoration is not merely an architectural revival; it is a reclamation of memory, bringing back the vibrant elegance that once characterized this “Little Jerusalem” at its height.

Echoes of a Cosmopolitan Past

Today, walking through the Essaouira Mellah is a quieter experience. The merchant houses, with their grand but faded doorways, now overlook streets less crowded. Yet, the spirit of the place is palpable. The restoration of Slat Lkahal stands as a beacon of cultural preservation and a poignant reminder of the community that built it. The sea breeze still sweeps through the streets, carrying with it the echoes of a time when this was a thriving, cosmopolitan hub where Jewish merchants shaped the destiny of an entire city.

The Essaouira Mellah offers a narrative not of secluded tradition, but of open, global engagement—a story where faith and commerce, protected by royal decree, created a “Little Jerusalem” that, for a glorious moment, looked out confidently onto the wide Atlantic.

Sacred Pilgrimage Sites: Layers of Memory and Miracles

Beyond the bustling Mellahs, Morocco’s spiritual landscape is dotted with sacred sites that speak to the deep, intertwined history of its people. These tombs and sanctuaries, often nestled in unexpected places, serve as powerful destinations for pilgrimage, where faith, legend, and history converge across confessional lines.

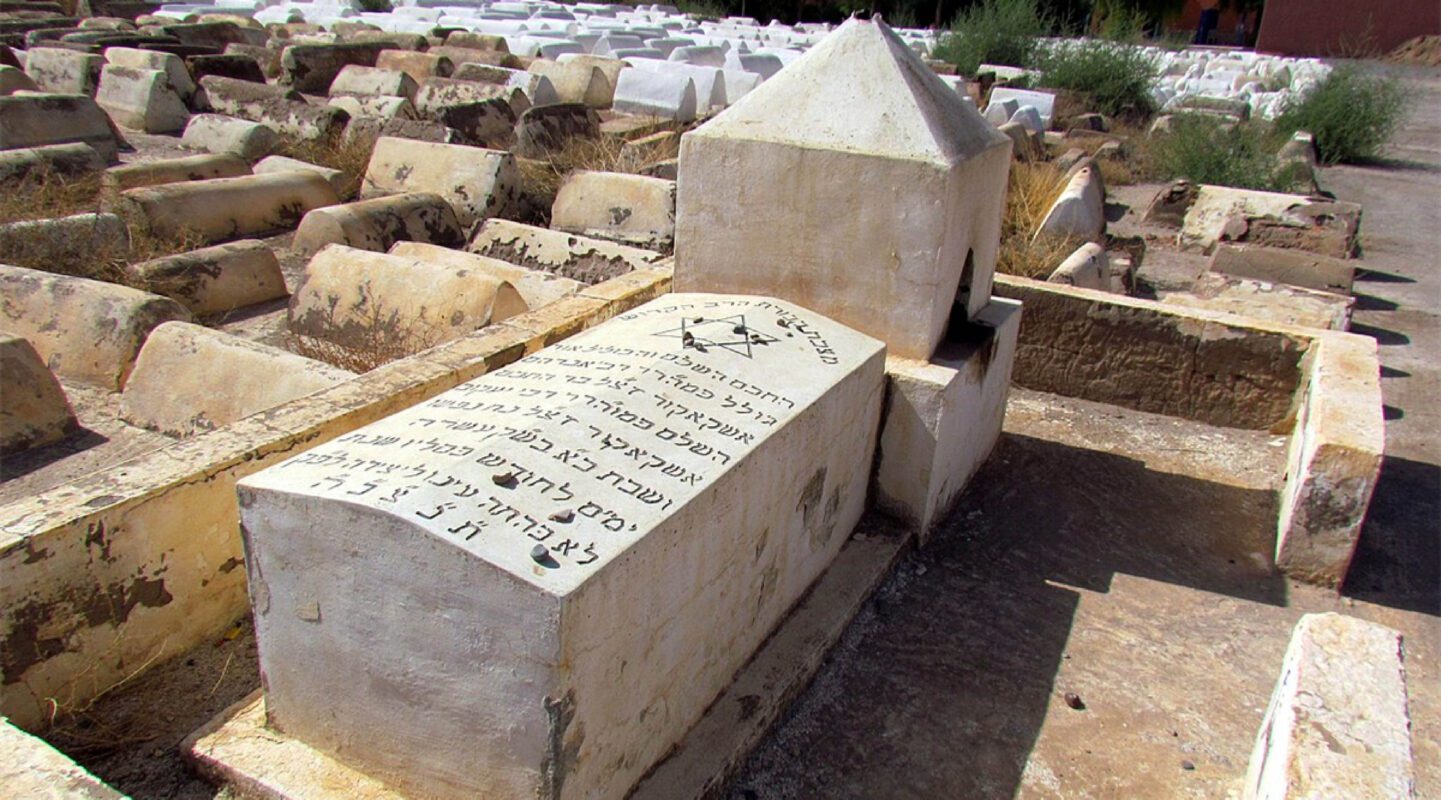

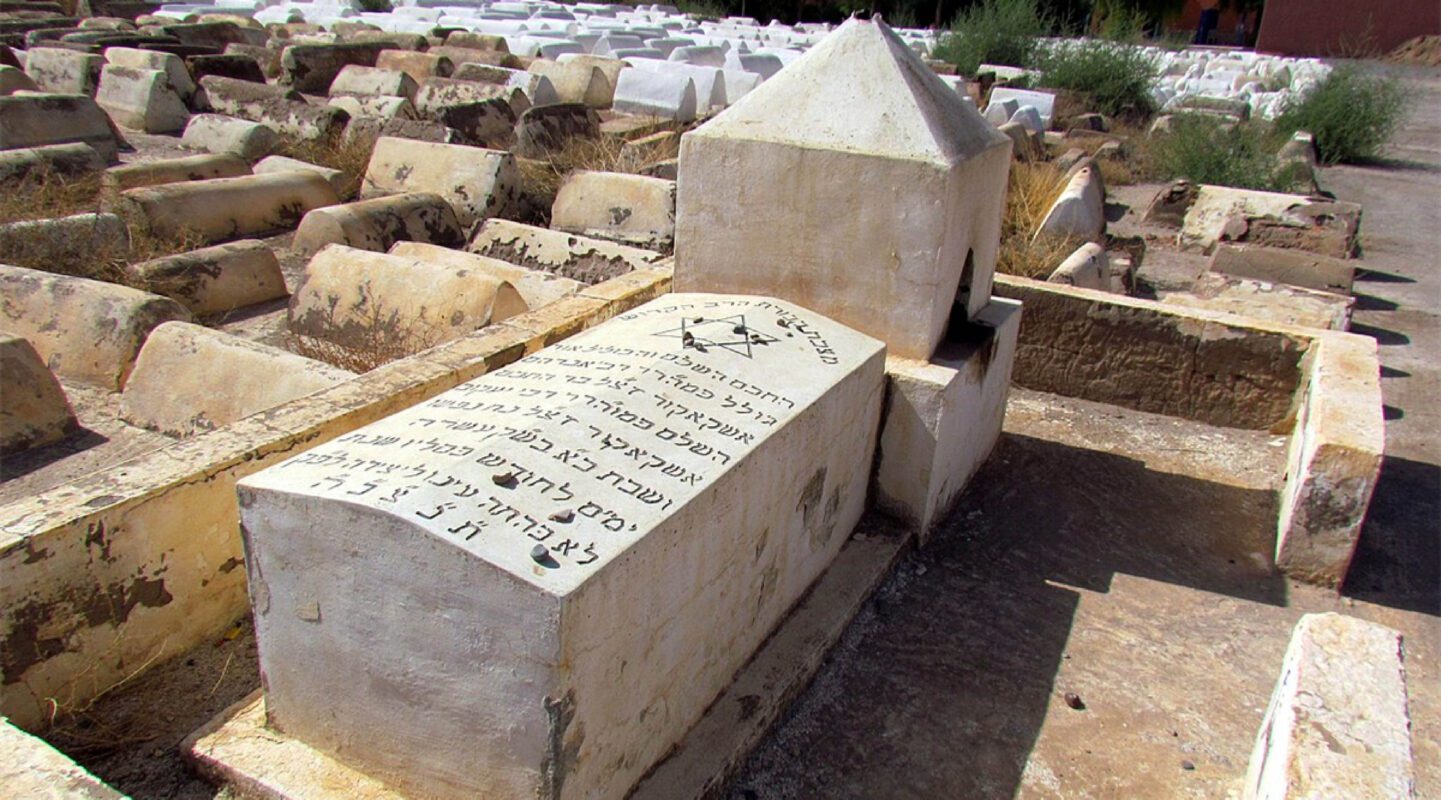

Rabat: The Chellah Necropolis – A Tapestry of Civilizations

These weathered sandstone markers, inscribed with Hebrew lettering, are nestled amongst the ruins, shaded by gnarled fig trees and prickly pears. The presence of these tombs within a broader Muslim sacred space is a poignant testament to the long-standing Jewish presence in the region. Pilgrims and visitors here do not just witness a single history, but a palimpsest of civilizations—Roman, Islamic, and Jewish—all coexisting in silent, ruinous harmony. The air is thick with the scent of flowering bushes and the distant murmur of the city, creating a space for reflection on the enduring nature of memory and rest.

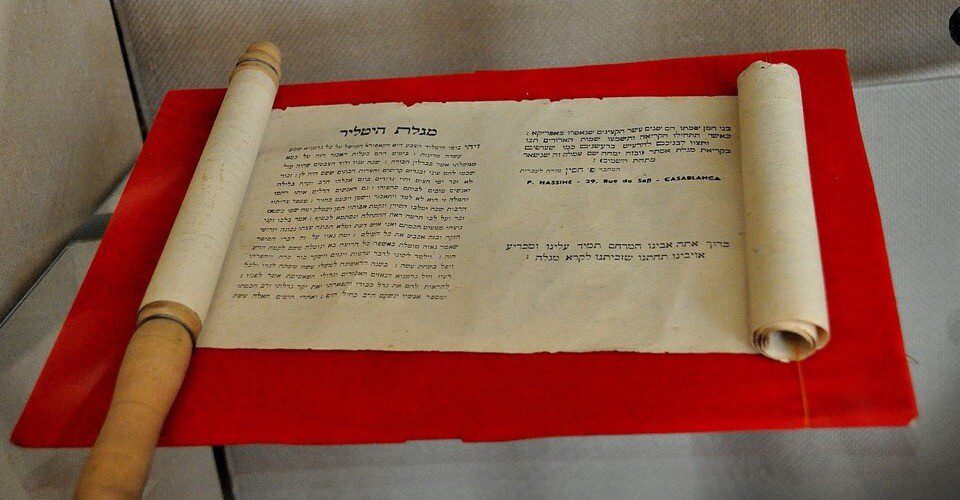

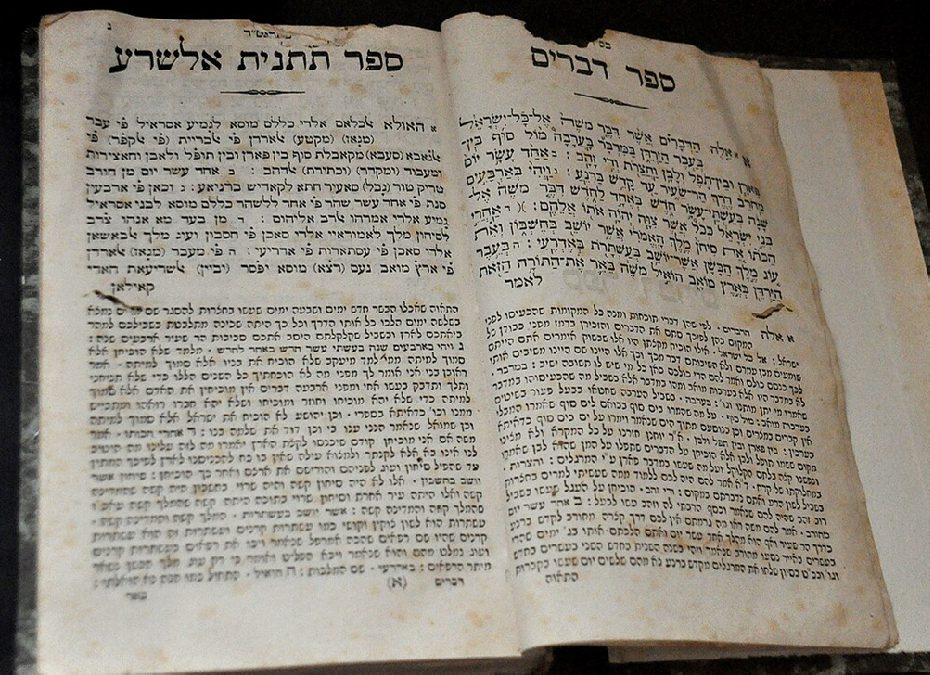

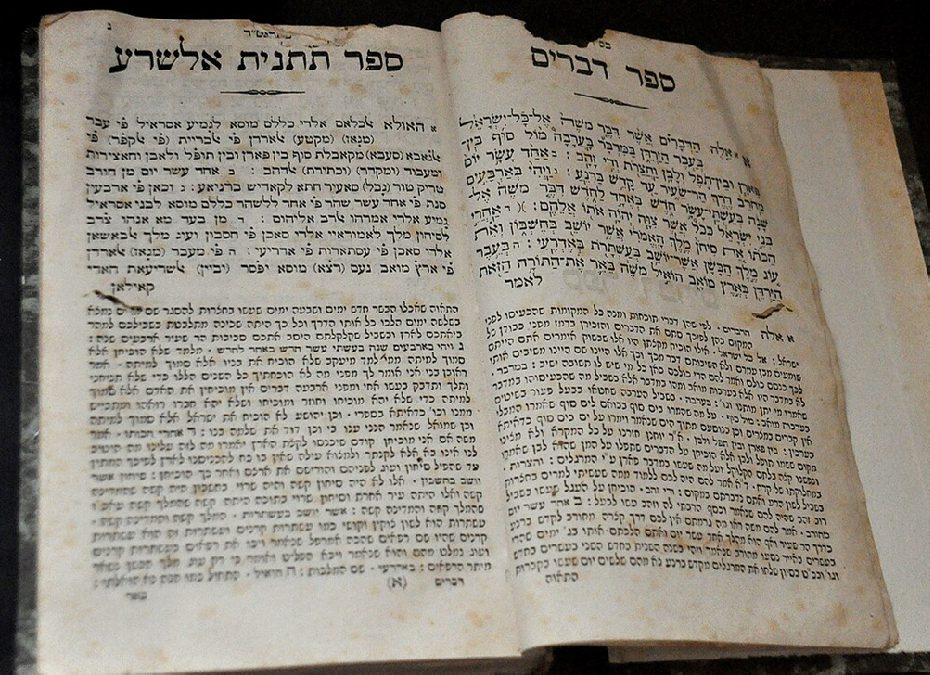

Fes: The Rabbi Shlomo Ibn Danan Synagogue – A Legacy in Parchment

While the Ibn Danan Synagogue in the Fes Mellah is famed for its architecture and mikveh, its true, beating heart lies in its role as a guardian of an extraordinary intellectual heritage. Within its protective confines, the synagogue safeguards some of the most precious 800-year-old illuminated manuscripts in the Jewish world.

These are not merely old texts; they are masterpieces of Sephardic art and devotion. Meticulously handwritten on parchment or vellum, they are adorned with vibrant colors, gold leaf, and intricate micrography—a decorative art form using minuscule Hebrew letters to create geometric and floral patterns. The manuscripts include prayer books, legal codes, and philosophical treatises, many of which were brought by refugees from Spain in 1492 or produced in the esteemed study houses of Fes itself. To be in the presence of these volumes is to stand a breath away from a golden age of Jewish learning. They represent an unbroken chain of scholarship and a desperate, successful struggle to preserve a culture’s most sacred treasures through centuries of change.

The Enduring Cultural Legacy of Moroccan Jewry

The Jewish presence in Morocco, spanning centuries, has left an indelible mark that extends far beyond the walls of the Mellahs. This legacy is not a separate history but a golden thread woven deeply into the very fabric of Moroccan national identity, most vividly seen in the shared realms of food, music, and art.

Culinary Fusion: A Shared Table

Skhina (or Dafina): This is the quintessential Sabbath stew, a slow-cooked masterpiece designed to simmer overnight in the embers of a public oven, respecting the prohibition against lighting a fire on the day of rest. Packed with wheat berries, chickpeas, potatoes, meat, and eggs, and delicately spiced with cumin and pepper, its name derives from the Arabic word for “hot” or “warming.” Its complex, deep flavors are a direct result of this unique cooking process, and variations of this dish are now enjoyed by Moroccans of all backgrounds as a comforting winter delicacy.

Maakouda: These savory potato fritters are a ubiquitous street food snack across Morocco. Simple, affordable, and irresistibly delicious, they exemplify how a Jewish culinary staple became a national favorite. Often sandwiched in fresh bread with a spicy harissa sauce, the maakouda’s journey from a simple home kitchen to the bustling souks symbolizes the effortless integration of Jewish culinary contributions into the daily life of the country.

Music: The Andalusian Bridge

The musical tradition of Morocco is one of its greatest treasures, and at its heart lies Andalusian classical music (Al-Âla). This sophisticated art form, developed in the courts of Al-Andalus (medieval Islamic Spain), became a shared cultural sanctuary for Muslims and Jews after their expulsion during the Reconquista. Jewish musicians were not merely practitioners but were often revered masters and innovators of the tradition.

They preserved and composed countless Hebrew liturgical poems (piyyutim) set to the complex melodic system of the Arabic maqam scales. The maqam, with its specific emotional and spiritual resonances, provided the perfect vessel for Hebrew poetry of devotion and longing. To listen to a piyyut sung in the Andalusian style is to experience a profound cultural synthesis—the soul of Jewish prayer expressed through the intricate, haunting musical language of the Arab world. This shared repertoire remains a powerful, living symbol of a common heritage that transcends religious divides.

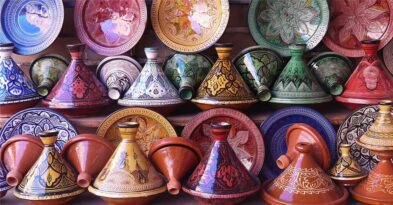

Architecture: A Synagogue of Synthesis

Upon entering, the eye is immediately drawn to the stunning zellij tilework. This quintessentially Moroccan craft, involving the precise assembly of hand-chiseled, glazed terra-cotta tiles into breathtaking geometric patterns, adorns the walls and floors. The vibrant blues, greens, and whites are a hallmark of Moroccan Islamic art. Yet, integrated seamlessly within this familiar visual field are sacred Hebrew inscriptions—verses from the Torah and Psalms—carved in stone or formed from the tiles themselves.

This is not a mere juxtaposition but a true synthesis. The Star of David is framed by Arabesque motifs; the Holy Ark is crowned with a shape reminiscent of a Moroccan royal minbar (pulpit). This architectural style proclaims that one can be fully Jewish in faith and fully Moroccan in artistic expression, creating a sacred space that is both distinctly Jewish and authentically, beautifully Moroccan.

Modern Renaissance: Reclaiming a Pillar of National Identity

In a region often marked by the erosion of Jewish heritage, contemporary Morocco stands as a profound exception. Under the visionary leadership of its monarchy, the nation is experiencing a remarkable renaissance of its Jewish history—not as a relic of the past, but as a living, celebrated component of its modern identity. This conscious revival is a multi-faceted endeavor, spanning cultural institutions, spiritual traditions, and direct royal patronage.

A Beacon of Coexistence: The Museum of Moroccan Judaism in Casablanca

The Unbroken Chain: Annual Pilgrimages to Saints’ Tombs

Perhaps the most vibrant testament to the enduring spiritual connection is the continuation of annual pilgrimages, known as Hillulot, to some 126 saints’ tombs scattered across the country. These sites, honoring revered rabbis and holy figures, have for centuries been focal points of devotion, believed to be places where heaven and earth meet. Despite the diaspora that saw most Moroccan Jews resettle in Israel and France beginning in the mid-20th century, this sacred tradition has not been broken. Each year, thousands of their descendants return on charter flights, pilgrimaging to cities like Ouazzane, Demnate, and Essaouira.

These events are profound cultural and religious homecomings. The air fills with the sounds of piyyutim (liturgical poems) and the smells of traditional foods. The scenes at these hillulot—of Moroccan Jews dancing with their country’s flag alongside the Israeli one, welcomed warmly by their Muslim neighbors—are a powerful spectacle of uninterrupted memory and a unique model of transnational, interfaith connection rooted in a shared homeland.

Royal Protection: The King as Guardian of Heritage

Furthermore, in a groundbreaking move, his government has officially included Hebrew language and Jewish heritage and culture in the national curriculum and heritage programs. This institutionalizes the teaching of this history to a new generation of Moroccans, ensuring that the story of their Jewish compatriots is understood not as a footnote, but as a fundamental chapter in their national narrative. Through this top-down patronage, King Mohammed VI is not only preserving physical structures but is actively nurturing the cultural and historical soil from which a truly inclusive Moroccan identity can grow for the future.

The Moroccan Jewish experience represents a unique model of religious pluralism, where “dhimmi” (protected people) status historically allowed Jewish communities to flourish as physicians, diplomats, and artisans under successive dynasties. Today, though the population has diminished from 265,000 in 1948 to about 2,000, their legacy endures in street names, musical traditions, and the royal commitment to preserving this essential thread in Morocco’s cultural fabric.

Contact us for more travel information!