The Moroccan Music

Morocco exists as a living mosaic of cultures, its identity forged by millennia of convergence. Berber heartbeats pulse alongside Saharan and sub-Saharan drumming, while whispers of Phoenician traders, Greco-Roman rituals, and Arab intellectual traditions blend with the refined melodies of Al-Andalus. This nation doesn’t just possess history—it embodies a continuous dialogue between continents.

Moroccans have rhythm in their blood. In a taxi, a market, or a home, music emerges spontaneously—from the tap of shoes on cobblestones, the jingle of coins, the percussive rhythm on an overturned pot. This innate musicality is a release from worry, a way to let sound course through the veins, forming the very soul of its culture, as in many African nations.

Arab Music evolves continuously, where modern Moroccan pop absorbs contemporary sounds from across the Arab world (Egypt, Lebanon), creating a vibrant, evolving genre.

Andalusian Classical Music, the “classical” heritage of Al-Andalus, is passionately preserved in the unique Arabic dialects of each city. It is performed by distinct schools from Fez, Rabat, Tetouan, and the Gharnati style of Oujda.

Amazigh (Berber) Folk Traditions form the bedrock. From the Rif Mountains comes Reggada—a powerful musical and dance style from the northeast. Characterized by rhythmic foot-stomping and mock rifle movements (bandits), it reflects the warrior culture of the Rifian Berbers. This energetic style, also known as Aarfa or Imdiazen, remains immensely popular.

When Gnawa musicians pluck the guembri, Sufi dancers whirl into spiritual ecstasy, and nomadic hymns echo in desert tents, one understands: every corner of Morocco tells the same eternal story of cultural fusion, each in its own unique key.

Arab-Andalusian Music

Originating in medieval Al-Andalus, this treasured musical tradition found new life through the diaspora of refugees, blossoming into distinct regional styles across eight Moroccan cities. Each center developed its own character: the solemnity of Meknes, the intricacy of Fez, the elegance of Rabat, the earthiness of Salé, the maritime lyricism of Tangier, the spiritual refinement of Tetouan, the vast melancholy of Oujda, and the crystalline purity of Chefchaouen. Together, these cities form a living symphony of civilization, their variations preserving a lost world.

This music miraculously preserves fragments of medieval Spanish (Ladino) lyrics, occasionally interwoven with Hebrew verses, serving as a living fossil of an era when three faiths coexisted. While formally established in the Maghreb in the 16th century, its soul was forged in the crucible of Cordoba’s Caliphate—a unique fusion of Arabic poetic spirituality and Iberian folk wisdom, born from the encounter between Islamic and Christian civilizations.

Its lyrical architecture is a triad of forms:

Muwashshah: Intricate classical poetry, woven like golden embroidery.

Zajal: Vernacular oral poetry, brimming with street humor and earthly wisdom.

Religious Odes: Bridging mystical yearning and secular emotion.

The musical core consists of suites called Nûba, legendary cycles said to have originally numbered twenty-four, mirroring the hours of the day. Only eleven survive today, each a universe of emotion: the “Ramal” suite evokes dawn’s first light, “Maya” carries twilight’s gravity, and “Hijaz” bears the nomad’s longing. When the oud strings tremble and the daff drum resonates, these surviving musical constellations continue to swirl under Moroccan skies, each note a tunnel back to Al-Andalus’ golden age.

The Berber Music

Amazigh (Berber) music, much like the watersheds of the Atlas Mountains, branches into distinct regional dialects shaped by topography and tradition. This majestic range, stretching from the outskirts of Fez in the north to the desert fringes of Guelmim in the south, cradles unique musical idioms in each of its valleys.In these lands where life moves to the rhythm of nature, music transcends mere artistry to become a form of elemental dialogue. When crops thirst for rain, communities unite in chanting the Ahwach to summon clouds; when storms rage uncontrollably, specific drumming patterns are strictly forbidden to avoid exacerbating nature’s fury. Here, music acts as a regulator of natural breath—a force that can imbue wilting crops with divine spirit or restore life to a drying spring.

Amazigh music is deeply interwoven with the farming cycle, creating a unique “sonic almanac”:

Sowing Season: Stringed instruments are often prohibited, lest their vibrations disturb the spirits within the soil.

Harvest Time: The communal Bendir frame drum is played en masse, its vibrations believed to shake loose the abundance from the stalks.

Winter Dormancy: The Nafir long trumpet is blown, its raw, piercing tone meant to drive away the harsh cold.

This profound connection to the land makes any systematic classification of Amazigh music inherently challenging—it is not merely performance art, but a vital ritual for community survival.

The apparent chasm between Arab and Amazigh music often stems from an urban-centric narrative. While refined Andalusian Nawbas dominate in the courts of Fez and Rabat, the Arab folk music of the hinterlands possesses its own untamed power. The true distinctions lie deeper:

Instrumental Philosophy: Amazigh music often lacks professional musicianship; collective dance and song take precedence, with the Guembri lute and body percussion (clapping, foot-stomping) forming the core rhythm, rarely featuring the stringed instruments prevalent in Arab music.

Embodied Expression: Every Amazigh melody is intrinsically linked to specific dance movements; musical phrases and physical gestures exist as a symbiotic whole.

If Arab music seeks spiritual elevation through the poetic strings of the oud, the Amazigh people channel the pulse of the earth through the stomping of their feet—one aspiring for the heavens, the other rooted in the soil, together forming the inseparable dual soul of Morocco.

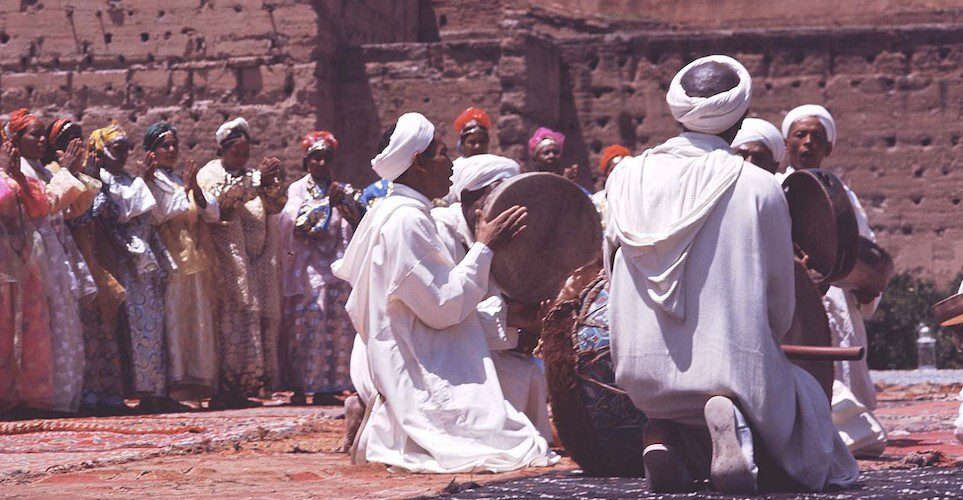

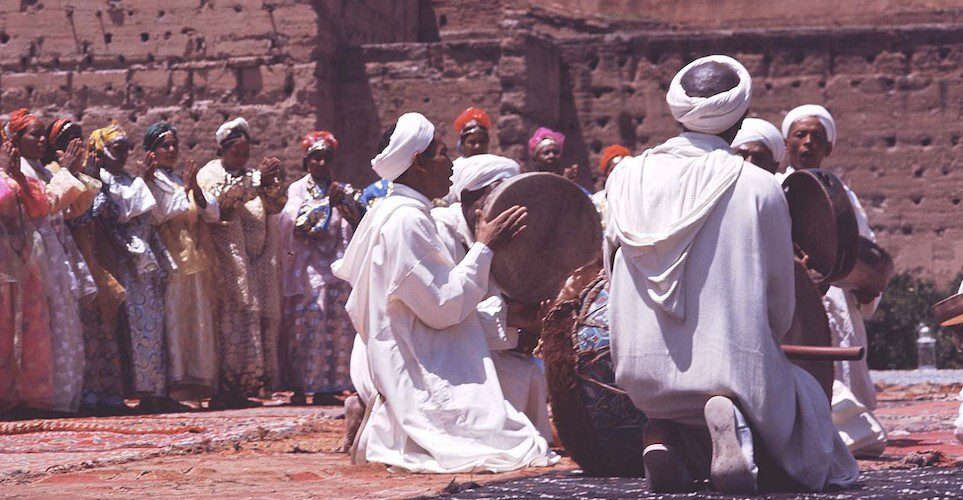

The Gnaoas (or Gnâwas)

Gnawa music stands as a unique cultural phenomenon specific to southern Morocco, particularly flourishing in Marrakech, Essaouira, and the vast southern regions. Its lyrics, like the genetic code of descendants of enslaved Africans, weave together Arabic, Amazigh, and African dialects, narrating a collective memory that spans the Sahara.

From the 12th century onwards, enslaved people from Senegal, Mali, Nigeria, and other sub-Saharan regions were brought to Morocco, serving as both soldiers for the Almohad armies and builders of its palaces. These uprooted souls founded secret brotherhoods (confrèries) in their new land, centered around master musicians called mâalems. Through initiation rites that fused African rituals, Arab Sufism, and Berber traditions, they sought spiritual belonging in trance-inducing dances.

Gnawa is, at its core, spirit music:

The qraqeb (metal castanets) mimics the clanking of chains.

The guembri (a three-stringed lute with a camel skin soundbox) produces vibrations that resonate deep within the body.

The tbels (large drums) beat like a primal heartbeat.

When the music begins during nocturnal healing ceremonies known as lila (meaning “night” in Arabic), practitioners dance through sequences corresponding to seven rhythms, each associated with a color and spirit: white for benevolent spirits, red to awaken warrior souls, black to connect with the underworld. This sunset-to-sunrise ritual is both a form of music therapy and a vital act of cultural preservation.

Gnawa has undergone a remarkable transformation in the modern era:

The annual Essaouira Gnawa and World Music Festival attracts artists and pilgrims from dozens of countries.

It engages in improvisational dialogues with jazz, shares its lament with the blues, and finds common ground with reggae.

Its narratives are repurposed in Moroccan rap, giving voice to contemporary struggles.

From secret gatherings in slave quarters to its inscription on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, Gnawa has composed a powerful ode to freedom using its most painful notes, its spiritual resonance now an indispensable coordinate on the world music map.

The Chaabi Music

Chaabi music is a vibrant cultural crucible, forged from the genetic recombination of countless Moroccan folk traditions. Born in the bustling spaces between market stalls, its rhythm now pulses through every celebration—from desert wedding festivities around bonfires to Atlantic coast street parties, its vital pulse echoes everywhere.

The very composition of a Chaabi ensemble tells a story of cultural exchange:

Eastern elements like the darbuka goblet drum and Arabic tambourine.

Western imports like the mandole (a local adaptation, a large mandolin with a guitar-like sound equipped with four courses of metal strings).

The vertically held violin—continuing the playing posture of the traditional guembri.

The unexpected cameo of the banjo and the subtle textures of the piano.

This instrumentation blurs the lines between Eastern and Western music. Much like the tango rhythms played by Algiers’ pianists using Arabic scales, Chaabi is a hybrid by nature.

Unlike Raï, with its straightforward narratives of desire, Chaabi constantly seeks balance in a dialogue between ancient and modern. It channels the mystical verses of 14th-century Sufi poets while voicing the homesickness of contemporary immigrants; it preserves the narrative traditions of Amazigh troubadours while absorbing the romance of French chanson. As ukulelist Cyril Lefebvre observed, “The musicians play with a near-ferocious intensity, that raw emotional outburst connects Chaabi to the spirit of the blues.”

When the vertically-held violin cries out with passion, when the metallic mandole and the darbuka drum engage in rhythmic duel, Chaabi music achieves a deconstruction and reinvention of refined Arab aesthetics through the most grassroots means. Today, from underground clubs in Casablanca to wedding tents in Parisian immigrant neighborhoods, this “art of the people” thrives with weed-like vitality, sounding the modern heartbeat of North Africa across the globe.

The Samâa: the sacred songs

Samāʿa stands as Morocco’s most ancient form of spiritual music, constructing sanctuaries of sound through hymns praising the Prophet Muhammad and Allah. This sacred art flourishes not only in mosques and mausoleums during religious festivals but also flows through life’s pivotal moments—from a newborn’s first cry to the clamor of weddings, and even into the solemn silence of funerals. Samāʿa marks the sacred annotations of life’s cycle with its timeless melodies.

A complete Samāʿa night is a meticulously orchestrated spiritual journey:

Stage of Purification: It begins with the recitation of Al-Fatiha, the Opening Chapter of the Quran. Participants sit cross-legged, cleansing worldly thoughts through the rhythm of the sacred verses.

Stage of Entrancement: The lead singer opens with the welcoming hymn “Tala’a al-Badru ‘Alayna” (The Full Moon Rose Over Us), believed to have been sung upon the Prophet’s arrival in Medina in 622 CE. The voices rise like spiraling frankincense smoke.

Stage of Union: Participants repetitively chant the Divine Name “Allah,” swaying back and forth with the rhythm until reaching a state of selfless spiritual ecstasy.

The Samāʿa chorus is a living specimen of vocal archaeology:

8 to 40 singers require decades of training to master unique diaphragmatic breathing techniques and microtonal chanting.

Members must memorize thousands of traditional hymns, including versions in extinct Andalusian dialects.

The lead sheikh guides the swells and transitions of the vocal waves by tapping the floor with a sandalwood staff at specific frequencies.

When ancient hymns resonate in the courtyards of the University of Al Quaraouiyine in Fez, when chants in desert tents harmonize with the starry sky, Samāʿa is more than a musical performance—it is a journey of collective consciousness traversing time. In an era drowned by electronic music, these pure sound waves, guarded by ascetics, continue to offer eternal spiritual coordinates for wandering souls.

Raï

Rai—a musical seed that first sprouted in the soil of Algeria—spread like wildfire through Morocco since the 1960s, now deeply ingrained in the musical bloodstream of this North African land. It began as the protest sound of the slums in the port city of Oran and has evolved into a youth cultural wave sweeping across the Maghreb.

This innovation reached its peak in classics like Cheb Khaled’s “Aïcha”—a track that preserves the primal anguish of desert music while pulsating with the modern heartbeat of international metropolises.

Contemporary Moroccan musicians are pushing Rai into new dimensions:

Sampling Amazigh folk songs in Paris metro stations and processing ancient love ballads with Auto-Tune.

Deconstructing the ritual rhythms of Sufi whirling dances into electronic music drops.

Creating chemical reactions between the Gnawa guembri and 808 basslines.

When Rai remixes echo through underground clubs in Casablanca, and when young people breakdance to Rai rhythms beneath the ancient walls of Fez, this once-dismissed “voice of the lower classes” is actively reshaping North African identity with astonishing inclusivity. It is both the cultural nostalgia for second-generation immigrants and the rebellious manifesto of Gen Z, proving with its vibrant beats that true tradition achieves immortality through constant self-reinvention.

The new generation

As the last rays of sunlight graze the minaret of the Hassan II Mosque, the industrial warehouses of Casablanca awaken to the sound of Morocco’s musical future. A new generation of musicians is decoding and reconstructing millennia of cultural DNA—where Berber rhythms symbiotically merge with reggae downbeats, Andalusian scales are reborn on electric guitars, and Sufi chants transform into cosmic echoes through audio effects processors.

This annual summer festival in the old port district has long transcended mere celebration:

Stages converted from abandoned crane factories are adorned with giant Berber-patterned light installations.

Experimental theaters host dialogues between Gnawa rituals and breakdancing.

In markets beside artisan souks, rappers craft rhymes in Darija that tackle pressing social issues.

These young creators demonstrate a unique cultural strategy:

Metal bands incorporate the traditional ghaita reed instrument into progressive arrangements, unleashing Berber warrior cries through walls of distortion.

Electronic musicians dig into sample libraries for their grandmothers’ lullabies, reconstructing them into futuristic hymns with synthesizers.

Singer-songwriters trilingual lyrics suddenly pivot into ancestral Sufi throat singing during the chorus.

When a headscarf-wearing bassist swings her hair on stage, when descendants of traditional artisans code interactive music installations, this auditory revolution at the North African crossroads proves that the most authentic national identity is born from the most fearless embrace of globalization. The Boulevard des Jeunes is not just a venue—it is a sonic laboratory where every drumbeat writes the contemporary definition of “Moroccan-ness.”

Contact us for more travel information!